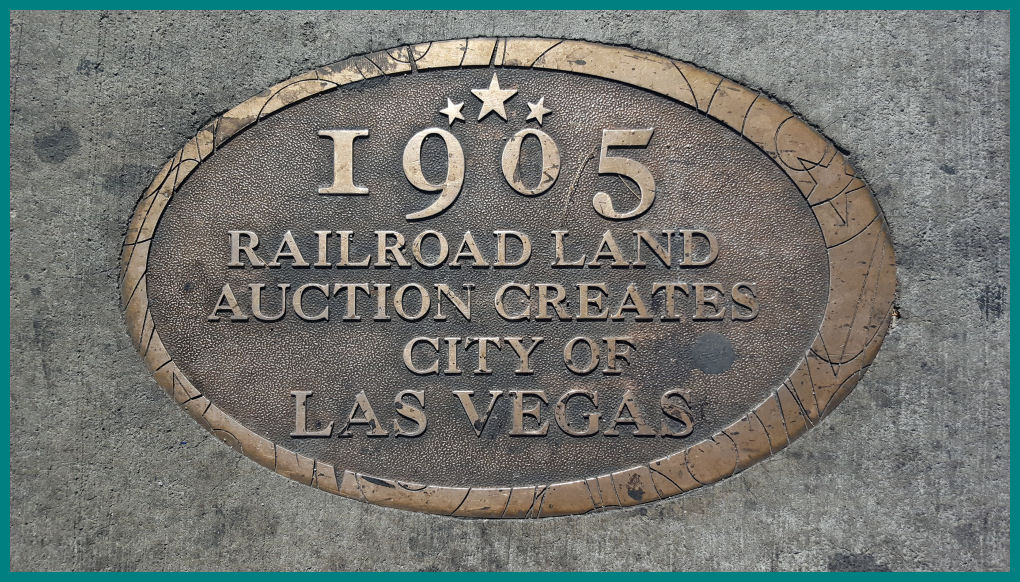

The Birth of Las Vegas May 15th 1905

The artesian springs, at the site of present-day Las Vegas, had been used by humans for about 15,000 years when in 1829 a band of New Mexican traders en route to Los Angeles came upon it. Chances are they had been directed there by Paiute or Ute peoples. The lush valley containing freshwater springs that they found was described in their native Spanish as las vegas.

The artesian springs, at the site of present-day Las Vegas, had been used by humans for about 15,000 years when in 1829 a band of New Mexican traders en route to Los Angeles came upon it. Chances are they had been directed there by Paiute or Ute peoples. The lush valley containing freshwater springs that they found was described in their native Spanish as las vegas.

Fremont Passes Through

The vegas remained largely unknown to the general public until May 1844, when explorer John C. Fremont made a note in his travel log of camping at the springs with his expedition party. Though only about half a dozen people followed in his footsteps in the spring, Fremont’s impact on the area would be remembered in the naming of Las Vegas’ main downtown street, Fremont Street.

The Mormons Build a Settlement

The first permanent settlement of the area did not occur until 1855, when about 30 Mormon missionaries, journeying from Salt Lake City, constructed a 150-square-foot adobe fort to establish a mail stop between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. The missionaries watched over the mail route, planted trees and gardens, and mined lead in nearby Potosi Mountain. Disagreements arose among them about the role of mining in their mission, and then it turned out that the lead was not pure, so in 1858, the mission was abandoned.

The Widowed Helen Stewart

In 1863 an Ohioan named Octavius Decatur Gass, also honored with a Las Vegas street, began acquiring land and ranching on it. At first successful, he soon fell into financial disaster and mortgaged his land to Archibald Stewart. The ranch prospered for five years under his hand, but Stewart died in 1884 leaving the land to his wife Helen. The widowed Stewart remained on the land, working it with hired hands and providing rest for travelers and postal services for the area.

The Railroad Comes Through

The foundation for modern-day Las Vegas was laid in 1902 when U.S. Senator William Clark of Montana bought the rights to the former Mormon settlement from Helen Stewart. For $55,000, Clark purchased 2,000 acres worth of land and water rights in hopes of developing a town around his burgeoning San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad.

Land Auction

As workers arrived in the summer of 1904 to begin construction on his railroad, Clark announced that in May 1905 he would be auctioning off lots, priced between $150 and $750, which he had divided from his 2,000-acre plot, east of the planned tracks.

McWilliams Townsite

In anticipation of the construction of Clark’s railroad, another surveyor, J.T. McWilliams, had purchased 80 acres west of the planned railroad tracks. McWilliams began selling lots for $100 each at the end of 1904. By the time Clark’s railroad was complete in January of 1905, McWilliams’ town boasted more than one hundred buildings, including barbers, hotels and stores.

Luring Buyers

Spurred by the development of McWilliams’ competing townsite, Clark embarked on an aggressive campaign to lure prospective buyers to the area, promising those who bought land in the auctions a full refund on their $16 train fare. Newspaper advertisements for Clark’s Las Vegas Townsite urged prospectors to “Get into line early. Buy now, double your money in 60 days.”

Water Rights

Furthermore, to outdo McWilliams, Clark formed the Las Vegas Land and Water Company, assuring prospective buyers that once lots were purchased, the company would provide road, sewer, and water maintenance. He also refused to provide water to the McWilliams Townsite. In negotiating his purchase from Helen Stewart, Clark had bought all water rights for the area.

Failed Townsite

McWilliams’ Original Las Vegas Townsite, although bustling, lacked any promise of sanitation maintenance. The buildings, made from wood and canvas, caught fire frequently. Stockyards brimming with livestock brought hordes of flies. Most importantly, without access to water in the Nevada heat, McWilliams simply could not compete with Clark.

3,000 Buyers

Clark’s plan paid off. Prospective buyers flocked to the area, building encampments along the Las Vegas Creek weeks in advance of the auction. By May 14, 1905, over 3,000 people had arrived in the area.

Fever Pitch

On May 15, 1905, in front of the makeshift train depot — a parlor car parked at the end of Fremont Street — investors began bidding for the coveted Fremont Street lots. Over the course of the day, the auction became increasingly intense. The heat and close quarters, coupled with the land-hungry atmosphere, caused the auctions to reach a fever pitch.

Bidding Wars

By the end of the day, the going price for some of the lots had reached twice their initial value. Some of the bidders, frustrated and angry at the skyrocketing prices, began to protest. The possibility of riots forced Clark to cancel the next day’s auction; he sold the remaining lots the next day for market price.

A Good Profit

The auction, typical for its time, had yielded more than $265,000 for Clark. In total, Clark sold more than 600 lots, at an almost 500 percent profit. Many businesses and civilians who had resided on McWilliams Townsite transferred to Clark’s side of the tracks. By the end of the auctions, scores of canvas tents that housed businesses on the west side of the tracks had relocated to the east and were setting up shop by the end of the day.

Duped

Once the frenzied atmosphere of Clark’s auctions died down, however, many of the investors who had purchased lots became impatient with the town’s seemingly slow growth. A month-and-a-half after Clark’s auction, two dozen of the investors had abandoned their lots, convinced that Clark had duped them into buying worthless land.

Block 16

Still, many stayed. The railroad maintenance shop employed between 400 and 800 workers at various times. Eventually, more permanent forms of construction cropped up; brick and stone establishments, schools, and pharmacies were built. One of the biggest draws in the town was Block 16, where liquor, prostitution, and gambling were legal. Block 16 catered to the repair yard workers, but weary travelers and miners also flocked to the saloons for refreshment while their trains stopped in the town for maintenance. Soon, Las Vegas became a popular and bustling place.

Uncertain Future

With the end of World War I, however, the need for Nevada’s mining industry diminished. In 1922, the city joined the national railroad strike; in 1927 the Union Pacific left town as payback. The majority of Las Vegans worked for the railroad. When the railroad shut down, so did the town. The once busy Fremont Street grew quiet and many businesses went bankrupt. Still, in its infancy, Las Vegas’s future was uncertain.

Sources:

The City of Las Vegas, the Early Years