HUNTRIDGE ON MARYLAND

A VACANT THEATER BEARS SILENT TRIBUTE TO THE TRUE FOUNDERS OFTHE LAS VEGAS STRIP

On the busy corner of Charleston Boulevard and Maryland Parkway in Las Vegas stands the streamline moderne, 1940’s architecture of the abandoned Huntridge Theater. Despite its listing with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, it has long been the subject of controversy, tempest tossed in disputes over its preservation since its 2002 closure.

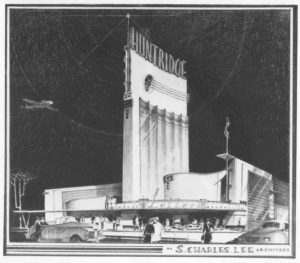

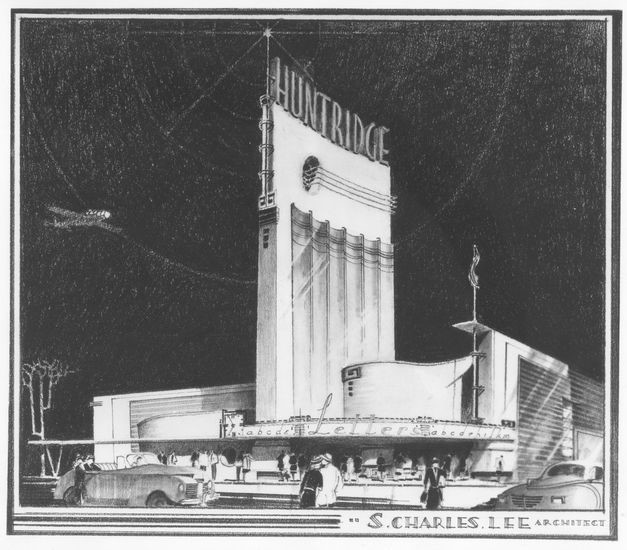

Huntridge is among the largest of theaters designed by S. Charles Lee, perhaps the most prolific of Hollywood’s celebrity architects of the golden age of cinema. Long-time Las Vegans are often sentimental about it: The hipsters who enjoyed her as a concert venue in the 1990’s; the Generation X and baby boomers who relate first movies, first dates. An occasional recollection of the first racially integrated theater in town, ownership by movie stars, early visits by celebrities, and premiers. Few recall years prior to the 1950’s. None seem to know its genesis.

Huntridge Theater is most often recognized by its 75-foot concrete sign, the tallest in Las Vegas upon its 1944 completion. Considering the City’s population was only about 25,000 at that time of the crescendo of World War II, the 950-seat auditorium and trendy architecture are of baffling scale. Add to this lack of apparent feasibility the fact that planning and construction took place during the Office of Price Administration, the stringent World War II-era rationing of building materials and labor. At the time of completion, trash filled the streets of Paris, then rotting under Nazi occupation for four years. Anne Frank and her family had just been captured. Humphrey Bogart had just starred Casablanca. The Las Vegas Strip and the major Las Vegas residential thoroughfare of Maryland Parkway did not yet exist.

What brought about this seemingly impossible construction project at such an improbable time? What drove those who created it, as well as the Huntridge neighborhood, the first master planned community in Las Vegas, with its residential neighborhood stretching for blocks to the south of the theater? To find the catalyst we must go back. To unveil his motivations, back further still.

Hollywood movies often depict the genesis of Las Vegas as a grand vision of Ben “Bugsy” Siegel, or other characters of mafia folklore. But the truth is that Huntridge, and indeed much of modern Las Vegas sprang from the vision of a powerful figure so global in action, selfless in promotion and diverse in alliance that only fragments of his work appear in the history books:

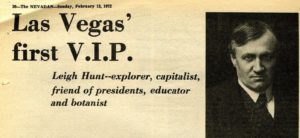

Leigh S. J. Hunt. Hunt was at the center of a group of American and European capitalists who in many ways defined global banking and industry from the late 1880’s to at least the 1940’s. He was a college president in Iowa, owned newspapers, mines - even started a town - in the

Washington territory before it became a state. He had created massive industrial mines in today’s North Korea, giant industrial farming operations on the upper Nile of the Sudan, sugar and cotton plantations in Mexico, industrial wheat farming in Alberta. When he settled in Las Vegas in 1923, Hunt was intent on exploiting the power and water anticipated with the promise of Hoover Dam, still 10 years off.  Photo and headline from The Nevadan Feb 13, 1972 , courtesy Nevada State Museum Archives

Photo and headline from The Nevadan Feb 13, 1972 , courtesy Nevada State Museum Archives

Leigh S. J. Hunt was first to promote the tiny railroad town of Las Vegas as being the coming resort center of the world4, and in 1925 his global group of moneyed followers joined in. Among

the original investors in the Las Vegas Strip and Huntridge were Teddy Roosevelt’s commander of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Willard Brownson; the former Adjutant General of the Sudan,

General Sir J. J. Asser; the inventor of modern gypsum drywall, Joseph F. Haggerty; the former Director of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Walter McLallen; the son of the developer of the modern New York Stock Exchange, Frederic Bull; a financial advisor to Wm. Randolph

Hearst and early travel film producer, Leland J. Burrud; the namesake of Clark County, Nevada, Senator William F. Clark; the Scottish Barons Moncreiff; the principal architect of British Hong Kong, James Orange; and most substantial among them all, the American banker to Czar Nicholas II, Hunt’s closest friend, Harry Fessenden Meserve.

By 1933, over 4,000 acres, an area much greater than all of the rest of Las Vegas at the time, had been purchased by the Hunt consortium. It was in fact these global capitalists, behind the scenes men, with vast funds and disdain for the public eye, who cast the dye that produced the Las Vegas Strip. Theirs is also the DNA of Huntridge, where their roots run deeper still. The story begins a few generations earlier.

During the American Civil War, the French Envoy to the United States backed the Confederacy, spelling trouble for Lincoln. The influence of Paris on Southerners from Louisiana, the state purchased from France a generation earlier, was considerable. But into the vacuum created by the lack of support from the French envoy, another French aristocrat threw his hat. He was a supporter of the North, joining Lincoln’s cabinet, balancing the scales.

Pictured just to the right of President Lincoln in the photo of his second inauguration, is that French adviser. He sailed with Lincoln to negotiations ending the war and was present at the surrender at Appomattox. He was in the upper window next to Lincoln during the President’s final speech from the White House, and declined the President’s invitation to Ford’s Theater on that fateful Good Friday six weeks later. He was the Marquis Charles Adolphe de Chambrun.

Chambrun endeavored to bridge the divide with France for Lincoln, joining the President in what was initially an unofficial, unpaid capacity. In so doing, Chambrun followed the steps of a famous ancestor of his wife, and adhered to the directive both men followed: “Omnia reliquit servare rempublicam” (“He left everything to save the Republic”), the motto of an organization that today is little known, the Society of the Cincinnati . Chambrun’s inspiration was his wife’s grandfather, a French hero of the American Revolutionary War who was President

Washington’s dear friend, an earlier French aristocrat volunteer, the Marquis de Lafayette.

Formed in 1783 by officers in the American Revolutionary War including Lafayette, membership in the Society of the Cincinnati is passed on to this day only to their heirs. The name comes from Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a Consul of Rome who, on more than one occasion, was called upon in emergency to be dictator of Rome when an invasion loomed, then unexpectedly resigned the position as soon as the emergency was over and battle won, relinquishing absolute power and wealth. Cincinnatus isa long-revered example of the citizen officer who serves when duty calls, returning power to the people when his service is no longer needed. The City of Cincinnati, named by a member, takes its name from this Society. As his wife was a direct descendent of Lafayette, the Marquis de Chambrun was a renowned friend of the Society of the Cincinnati. His heirs would be members One such heir was his middle of three sons, Count Aldebert de Chambrun.

In May of 1940, Count Aldebert was waiting for his wife, Countess Clara Longworth de Chambrun, an American from Cincinnati and cousin of President Franklin Roosevelt, to arrive at the Count’s Paris office at National City Bank. The Countess hurried along the Champs Elysee as the Nazis destroyed everything in their path, roaring into the City of Light. Millions of Belgian refugees joined the French, fleeing southward in a massive traffic jam by foot, horse, bicycle, car; a river of humanity frantically escaping the Nazi blitzkrieg.

Count Aldebert was of particular interest to the invading force. A celebrated General of World War I, the aging aristocrat held dual US and French citizenship, as do all descendants of Lafayette. He was a director of the American Hospital of Paris, as well as the Paris branch of National City Bank of New York. His thespian wife, a Cincinnati native, ran the American Library in Paris. Bank Intelligence identified the Count and Countess as targets for kidnapping by the Germans. Management ordered them out of Paris,asthe cannons thundered close. The Countess arrived at the Bank, but the driver assigned to transport and assist the senior couple had disappeared.

Years later, the Countess recalled at this moment the sudden appearance of a 53-year old bank trust officer who volunteered to take the place of the missing driver. Accommodations in Southern France, at the all-but-abandoned Château de Lavoûte-Polignac, a massive historic castle of the family of Prince Pierre of Monaco, had been arranged. But the safety of the castle was two days drive, overrun by refugees and devoid of fuel or provisions.

The Countess recalled the driver’s skill and vigilance as he watched over them en route south. Her memoir indicates little knowledge of this driver. But the man’s history would indicate that her husband surely knew more.

Initial foreign branches of the American bank from which the group departed in Paris had been opened in 1915 by National City Bank of New York’s unprecedented international expansion operation. It was then that its Vice President of foreign banking, Harry Fessenden Meserve, saw the first opening by any American bank of a branch on foreign soil, as National City opened in

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Meserve had a trusted emissary in Rio Named Henry Leigh Hunt, a second-generation globe-trotting entrepreneur with deepconnections around the world. Henry,

the son of Leigh S. J. Hunt, had lived in Rio for four years as company treasurer to one of the Bank’s largest clients. But Meserve had known the 29-year-old Hunt since childhood.

Meserve, who descended from a Lieutenant aboard the privateer Satisfaction during the

American Revolution, had graduated from Harvard in 1888 before heading west to the wilds of Seattle, “patiently waiting for the Country to grow”. There he became bank manager, friend and confidant of the charismatic young owner of the Seattle Post Intelligencer, Leigh S. J. Hunt. Unwilling to wait for organic growth, Leigh Hunt had founded a bank, railroads, the town of Kirkland and the Monte Christo Mine, within a few years of arriving in Seattle from Iowa. He was Seattle’s wealthiest citizen.

Then, in the panic of 1893, Leigh Hunt suffered the loss of all equity and business operations. Bankrupt but unsinkable, he set sail to establish mining operations in what is now North Korea, where he partnered with, among others, the Emperor of Korea himself. Hunt soon sent for Meserve to manage his massive Unsan Gold Mines near the Manchurian border, which Meserve did until 1908. In 1902 Leigh Hunt sold the majority of his stake and the two men went down in Seattle history when they surprised old Seattle investors with repayment in full.

Meserve invested with his friend again in about 1900, when Hunt took control of five million acres of the shores of the upper Nile in the Sudan, over a decade ahead of even T.E. Lawrence. There, Hunt and renowned partners, advised by the Vilmorin seed company of Paris, farmed hundreds of thousands of acres of their new creation, Egyptian Long Staple Cotton. That fortune lead to another project by Leigh S. J. Hunt, in the American desert southwest.

In 1925 Leigh S. J. Hunt’s son, Henry Leigh Hunt arrived in Las Vegas, new French wife in tow. The couple had stopped in Paris to wed, immediately upon their return from two years in Brazil.

Henry had lived in Brazil since 1911, but left in 1917 to serve in the American Army during World War I. Decorated by France for bravery at the Battle of Belleau Wood, experienced in international business and finance, Henry joined his father there with intentions of developing their massive land portfolio. But Great Depression would devour the family’s liquidity, leading to a financial rescue by the cash of his father’s old friend and partner, Meserve. Captain Henry Leigh Hunt returned with his wife and three daughters to Paris in 1931 when Meserve hired him to run the trust department at Paris branch of National City Bank of New York.

Henry Leigh Hunt, April 1925 | Alexandra Leigh Hunt collection

A Francophile since youth, having married into the renowned French botany family which advised his father in the Sudan, Henry Leigh Hunt lived well on his return to Paris. As his bank position took on escalating importance, his father died in Las Vegas in 1933. Henry’s wife, Louise de Vilmorin, had become an author whose work would weave its way into the very

Nin, Anaïs (1934-1937) Fire, from A Journal of Love, The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin. New York, San Diego, London. Harcourt Brace Company reads: “Last night was a frivolous night with Bill Hoffman, the Barclay Hudsons, Henri Hunt, and Hugh. Bright lights, savory dinner at Maxim’s, Cabaret aux

fabric of French culture. Though the two divorced in 1934,he remained close to her family and their circle of friends remained intact. Harry Fessenden Meserve, by then retired but still much involved and traveling for the Bank, returned to Las Vegas in 1935. There he worked with the Hunts’ stalwart local company secretary, and long distance with Henry, to develop the Hunt syndicate holdings.

World War II brewed in late-1930’s Paris, and Meserve and the other bank directors were no strangers to the dynamics. Henry Hunt, mysteriously holding a passport allowing expanded travel privileges, journeyed repeatedly back and forth between Switzerland and Paris. He met often with diplomats, military officers, captains of industry, entertainers and others, debriefing them for reports which he surreptitiously sent to his secretary in Las Vegas, who typed and forwarded them to stateside officers of the Bank. The flow of information included warnings of attacks on Poland, the border massings of unreported German troops, Nazi control of airplane engine manufacturing in Romania, capital flow, spies, informants, secret societies and more.

The reports continued almost weekly until 1940,when German tanks rolled on Paris. That’s when Henry Leigh Hunt volunteered to replace the driver of Meserve’s old friends, the Count and Countess Aldebert de Chambrun.

Arriving at Château de Lavoûte-Polignac, Hunt and the Chambruns found it adorned with finery, while devoid of fuel or food. Surrounding towns were overrun, stores emptied. Doubt and danger lurked on the roads as desperation set in. As the stay stretched into weeks, the Countess de Chambrun remembered it as a struggle to survive both hunger and depression. It was in this dark hour that she learned of the skills of Henry Leigh Hunt.

Henry had crisscrossed the globe in an incredible lifetime of adventure and intrigue. The Countess reported in her memoires: “Fortunately for us, our improvised chauffeur turned out to be anything but an amateur when it came to camping, roughing it, and taking the most clever and tactful contact with the inhabitants of whatever country in which he happened to be. We soon discovered the advantages he possessed in travel experience. Having explored the wildest parts of India and Thibet, the Sierras and the Rockies were to him mere child’s play. When we saw how he could make something out of nothing at Lavoûte-sur-Loire, we laughingly bestowed upon him the name of ‘Daniel Boone’.”

In the Countess’s lack of familiarity with Henry, we see his mysterious modesty and stoicism. She appears oblivious to the fact that her famous cousin, former first Lady Edith Roosevelt, had written about Henry in her own memoir, describing him heartbroken at the 1913 funeral of her young cousin Margaret Roosevelt, with whom Henry had an exuberant romance while sailing with Theodore Roosevelt on that President’s famed trip to South America. The Countess seems to also have been unaware that Henry’s father was adviser to President Theodore Roosevelt; that the Hunts had subsidised and hosted Teddy Roosevelt’sAfrican safari or that the earlier President Roosevelt had written of the bravery and fortitude of Henry Leigh Hunt, in letters decades before. Hunt’s marriage to literary giant Louise de Vilmorin, who was a close friend of the Polignac family members who typically resided in the castle, an author who almost surely would have been known to the Paris librarian Countess, seems to have escaped the Countess’s attention in her description of the mysterious Mr. Hunt.

Hunt negotiated provisions from the local townspeople, managed to fuel the castle, hunted and cooked the meals. He located a nearby radio operator to stay informed. When word came of an armistice, and a provisional government formed in Vichy, the party traveled there to seek return home. In Vichy, Hunt took the first train of the newly reestablished service back to occupied Paris.

With ex-wife Louise remarried to a Hungarian count and living abroad, Hunt had custody of their three daughters boarded with in Lausanne, Switzerland. Aged 9, 10 and 11, his daughters were already on their way to meet their father in Paris, as Hunt mobilized to help another friend of Meserve.

Count Charles de Chambrun, younger brother of Aldebert, was an Ambassador of France known for having sent the 1914 encoded message from St. Petersburg to the French President, notifying him that the Czar was then mobilizing against Germany, beginning World War I. Informed by an old friend, the Czar’s foreign minister Count Nicolas de Basily, that French encryption had been broken, Charles famously transmitted that message via De Basily’s Russian encryption instead. Thus the French President received the message before the Germans.This bold diplomatic work of the first world war had placed Charles de Chambrun on the enemy’s black list, in the second.

Charles’s informer, Count Nicholas de Basily was the diplomat who later drafted the abdication of Czar Nicholas II. He then fled the Russian revolution and traveled extensively, seeking to regain status. He married a beautiful American in Paris, fleeing before the Nazi invasion, much to the relief of his new wife’s father, none other than Harry Fessenden Meserve.

Charles and Aldebert de Chambrun had one more brother, the eldest, the Marquis Pierre de Chambrun. Pierre had been the sole vote against the formation of the Nazi-friendly Vichy government, after the invasion of Paris. Although middle brother Count Aldebert had been able to follow Henry back to Paris and resume his posts, including at the Hospital which soon became an underground railroad for escaping Jews and downed American pilots, his freedom was due in part to family connections. Aldebert’s own son, Count Rene, was married to the daughter of the head of the Vichy government - the very authority Rene’s uncle Pierre had famously opposed.

Charles de Chambrun thus treaded carefully between thedifferingpolitics of his brothers and nephew, seeking an exit from occupied Paris.

Charles found that exit on October 26, 1940, when he and his wife fled with Henry Leigh Hunt and his daughters. Hunt’s knowledge of the subways took them further than most knew one could travel in the underground, emerging to the waiting car of Count Aldebert de Chambrun, complete with privileged license plates. Though his daughters were French citizens, prohibited by the Nazi regime from leaving France, Henry Negotiated visas through the Vichy connections Aldebert’s son Count Rene. Henry then took the party to the Spanish border at Hendaye. There, guards rightly suspected a hidden Chambrun fortune and jewels. Henry’s daughter Alexandra remembered soldiers unraveling the braids she and her sisters wore, looking for hidden gems. “They looked right at them in the doll clothes boxes my sister carried. They thought they were toys,” she later remembered.

Henry Leigh Hunt and his daughters boarded the S.S. Exeter on November 3, 1940, setting perilous sail to New York. The Eldest Chambrun brother, Marquis Pierre, remained in Paris. In 1941, his son, Marquis Jean Pierre Francoise de Chambrun, arrived in Cincinnati carrying intelligence of German gunboats. Marquis Jean’s uncle Charles, after escaping Paris with

Henry, became an integral part of theFrench Embassy inWashington, D.C, before returning to the reconstruction of postwar Paris asa member of the Academie Francaise

In 1941 Hunt returned to Las Vegas and the large home of his parents, where his mother still resided. There he joined the family’s trusty corporate secretary, Walter Hunsaker, through whom he had been sending intelligence reports for years. Hunt picked up the reigns of the land-rich, cash-poor development efforts of his father and Meserve, who had died earlier that year. Newly flush with a mysterious capital infusion and owed tremendous favors by the War Department, Henry was able to facilitate the unlikely construction of the Huntridge Theater, named in memory of his Father. A family-friendly master planned development included a tree-lined avenue meant to recall the pre-Nazi Champs Elysees, traveling around a park and perfect rows of houses built to accommodate returning soldiers and their families. His Episcopalian sister donated land for the Christ Episcopal Church in the Huntridge Neighborhood. Henry, a devout Catholic, saw to the donation of the land for Saint Ann’s Church and Bishop Gorman High

School with the help of a friend and client of the Bank, Romy Hammes. Businesses named for Huntridge fell into the place across the street from the Theater, on a matching parcel. An oval-shaped park graced the center of the Huntridge neighborhood, with roundabouts. Crowning the entrance was the Huntridge Theater.

A complete ghost in his business dealings, Henry LeighHunt sawhis father’s vision realized. Hunt lands hosted the developments of the early Las Vegas Strip, including the El Rancho, Frontier, Stardust, Riviera, Sahara, Landmark, Thunderbird, Silver Slipper, Circus Circus, International and other hotels, as well as the Las Vegas Convention Center, Convention Center Drive, Las Vegas Country Club and much more. Appointed Honorary Consul of Monaco in 1956. Henry Leigh Hunt retired to France after selling his last large parcel on the Strip in 1963 to upstarts Merv Adelson, Harry Lahr and Irwin Molasky. Like others with whom he did business, these men never met the mysterious Mr. Hunt. Buried in a simple grave in a village not far from Versailles, he lies forever close to the love of his life, Louise de Vilmorin.

Mysterious to the end, Henry Leigh Hunt’s name and photo are almost nonexistent in the annals of his time. Hunt Street in Ames, Iowa shares the Huntridge namesake, as does the town of Hunts Point on Lake Washington. Leigh S. J. Hunt was advisor to Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover, his wife’s cousin. He was business partner of the Emperor of Korea and Booker T. Washington, at the same time. He lunched with Mark Twain and inspired Louise de Vilmorin. Yet the Hunt legacy remains largely unknown at the very place of his greatest impact.

In 1937, Jessie Noble Hunt, widow ofLeigh S. J. Hunt,traveled with friends to America’s newest, largest reservoir. The body ofwater created by America’s largest Dam had taken five years to fill. Sailing to the new lake’s center, Jessie fulfilled her husband’s last wish, sprinkling the ashes of the international titan who first envisioned it all. Leigh S. J. Hunt rests at Lake Mead, Nevada.

Huntridge Theater is an obvious tribute to Leigh S. J. Hunt. But Henry Leigh Hunt’s memorial to that theater’s primary investor Harry Fessenden Meserve, and perhaps to the Chambrun family, is less obvious, though larger. It lays hidden in plain sight, in the very parkway which transcends the area, beginning at the corner dominated by the Theater. Here, in Hunt’s own inspiration, perhaps we solve his riddle.

The source of the cash infusion evident upon the return of Henry Leigh Hunt to Las Vegas during World War II is uncertain. But Henry Leigh Hunt’s dangerous endeavors to bring to safety the family and fortune of the direct descendants of General Lafayette, the Chambrun family, speaks of dedication and loyalty. In the aerial view of the streets of the Huntridge neighborhood of the 1940’s, those familiar with the Society of the Cincinnati may find a familiar symbol. It was the Society which gave its founding President, George Washington, the medallion which came to be known as the Washington Eagle. Like the streets and parks of Washington, D.C, and those of Versailles, the eagle medallion was designed by original Society member

Charles L’Enfant. It remains to this day the emblem of the Society. An outline of this very symbol may be seen in the original layout of the streetsand parksof Huntridge. This historic design element has until now escaped public recognition.

Left: The Dress Medallion of the Society of the Cincinnati Right: Huntridge neighborhood streets, circa 1944.

Huntridge Theater can be seen in the upper center-right – Photos: Jonathan Warren collection

Count Rene de Chambrun, son of Aldebert and Clara de Chambrun, returned to France after World War II, with wealth sufficient to re-take possession of Château de la Grange-Bléneau, the castle of his forefather, the Marquis de Lafayette. When Count Rene died in 2002, he bequeathed his fortune to his Foundation. Five years later, a descendant of George Washington auctioned the original Eagle medallion for $5.3 million. The purchaser was the Josee and Rene de Chambrun Foundation. The Washington Eagle now rests in the castle of Lafayette.

Long after the American Revolution,the aging Marquis de Lafayette returned to the US in 1824. The triumphant homecoming successfully re-sparked the Society of the Cincinnati in its second generation of members. Upon his death ten years later, Lafayette was interred as he himself had arranged in detail, at the famed Picpus Cemetery in Paris, under earth brought to Paris from America. An American state from which that soil was gathered by Lafayette himself is the same state on which the old General landed to re-ignite the Society. It is also this state which was home to the regiment that Henry Leigh Hunt joined in World War I; the same state which holds the crypts of generations of the Meserve and De Basily families, side by side; the state with the town of Hunt Valley and a development also called “Hunt Ridge”. It is the state which granted honorary citizenship to all members of the Society of the Cincinnati, and that in which Lafayette gathered his men to make his tide-turning attack on Yorktown, effectively sealing the defeat of the British in the American Revolution. It is not difficult to see that it was for this state and these relationships that Henry Leigh Hunt named the tree-lined thoroughfare which originated at Huntridge Theater, conceived by his father as the new city’s residential promenade, its nucleus, its mysteriously named centerpiece, Maryland Parkway.

Posted with permission.

Jonathan Warren has resided in Las Vegas for 48 years. He is the Honorary Consul of Monaco, the Chairman of the Liberace Foundation, was the Founding President of the Academie Francophone de Las Vegas. This article is based on his upcoming book, The Consul of Monaco: A forgotten global dynasty that spawned modern Las Vegas .