Fremont Street – First Paved Street in Las Vegas, Nevada

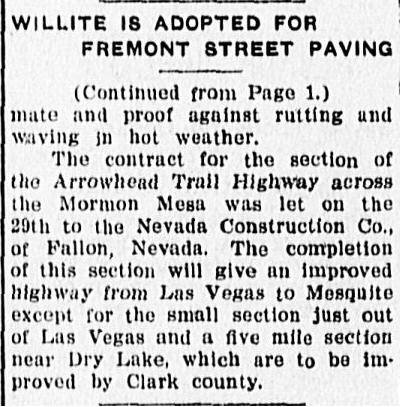

Did you know Fremont Street was the first paved street in Las Vegas? In 1925, the famous street was paved from Main Street to Fifth Street. The picture is a view from 4th and Fremont, circa 1925. The first stop light was installed in 1931. (Photo courtesy of UNLV Libraries Digital Collections)

Did you know Fremont Street was the first paved street in Las Vegas? In 1925, the famous street was paved from Main Street to Fifth Street. The picture is a view from 4th and Fremont, circa 1925. The first stop light was installed in 1931. (Photo courtesy of UNLV Libraries Digital Collections)

Like the city it long has symbolized, Fremont Street was built and transformed within the span of a single century. Long known as “Glitter Gulch” for its bright lights, Fremont Street is the heart of downtown Las Vegas and, next to the Strip, the second most recognizable street in southern Nevada. It also is central to an effort to redevelop downtown; a necessity arising from the Strip’s overwhelming success and the decline that afflicts most of America’s older urban areas.

When the Union Pacific Railroad and Senator William Andrews Clark auctioned off the Las Vegas Town site on May 15, 1905, Fremont Street was destined for big things. The railroad—originally known as the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake—built a mission-style depot at Main and Fremont, making that intersection the center of the small town. Not only was the railroad the major employer, but the depot eventually added a restaurant, the Beanery, which became a favorite dining spot for early Las Vegans.

The town’s founders expected Fremont Street to serve as Las Vegas’s central business district. It worked out differently than they expected. The railroad and its subsidiary, the Las Vegas Land and Water Company, banned liquor sales outside of Block 16 and Block 17, at the north end of the townsite along Stewart Street. However, a loophole allowed any establishment with a hotel room to sell alcohol, which led to the construction of several small hotels and liquor stores along Fremont Street and on other avenues. The bar owners of Block 16 had to turn to prostitution to compete for business.

More important, Fremont Street became not just the central business district but the small town’s central street. As Las Vegas’s population grew from less than 1,000 in the first official census in 1910 to more than 8,400 in 1940, the leading residential area would be along Fremont Street between Fourth and Fifth (now Las Vegas Boulevard, the street that turns into the Strip). Two early pioneers, Las Vegas Land and Water Company executive Walter Bracken and Las Vegas Age owner Charles P. “Pop” Squires, built homes there, and demonstrate that Las Vegas was a small town and that Fremont Street combined business and residential development. Squires operated the Age out of an office across from Bracken’s house. Banker John S. Park lived in a fashionable home at the northeast corner of Fourth and Fremont for many years, while Dr. Roy W. Martin, long one of the town’s two main doctors and a builder of the old Las Vegas Hospital, resided at the southwest corner of Fifth and Fremont.

More important, Fremont Street became not just the central business district but the small town’s central street. As Las Vegas’s population grew from less than 1,000 in the first official census in 1910 to more than 8,400 in 1940, the leading residential area would be along Fremont Street between Fourth and Fifth (now Las Vegas Boulevard, the street that turns into the Strip). Two early pioneers, Las Vegas Land and Water Company executive Walter Bracken and Las Vegas Age owner Charles P. “Pop” Squires, built homes there, and demonstrate that Las Vegas was a small town and that Fremont Street combined business and residential development. Squires operated the Age out of an office across from Bracken’s house. Banker John S. Park lived in a fashionable home at the northeast corner of Fourth and Fremont for many years, while Dr. Roy W. Martin, long one of the town’s two main doctors and a builder of the old Las Vegas Hospital, resided at the southwest corner of Fifth and Fremont.

As World War II brought growth to Southern Nevada—the local population tripled during the 1940s—Fremont Street changed. After wide-open gambling became legal in 1931, small casinos began to dot the street, especially in the three blocks between Main and Third. The first casino licensed after the 1931 law passed, the Northern Club, was at 15 East Fremont, between Main and First (in the multimedia presentation, its location is where the Coin Castle was in the opening shot). John Kell Houssels opened the Las Vegas Club a few doors away, and several other casinos and small hotels followed during the 1930s and 1940s, mostly with Old West-style names like the Boulder Club, the Apache, the Monte Carlo, the Frontier Club, and the Pioneer Club—all reflecting what was then a conscious effort by Las Vegas leaders to market their town as western-style. Two of downtown’s legendary casinos opened during the early postwar boom—the Golden Nugget at the southwest corner of Second and Fremont in 1946 and Binion’s Horseshoe on the ground floor of the Apache Hotel on the northwest corner of the same intersection in 1951.

As if to show how the Las Vegas populace was evolving, the ownership of Fremont Street’s casinos changed too. Most of the 1930s operators had been involved in small casino operations elsewhere or had wandered into the business: onetime mining engineer J. Kell Houssels Sr. operated the Las Vegas Club, while Mayme Stocker was the Northern Club’s licensed owner, allegedly because the Union Pacific Railroad, for which her husband and sons worked, frowned on its employees entering the gambling business. In the 1940s, more of the casino bosses were also involved in other illegal activities, such as Prohibition-era bootlegging. For example, Los Angeles vice cop Guy McAfee ran the Frontier Club and Golden Nugget, and his Southern California allies Tutor Scherer, Farmer Page, Chuck Addison, and Bill Curland headed the Pioneer Club, which boasted the famous neon image of “Vegas Vic,” with a deep voice saying, “Howdy, Podner.” In the 1950s and 1960s, increasing numbers of downtown casino operators were tied to the Strip: Eddie Levinson had come to Las Vegas as a part-owner of the Sands and wound up with controlling interests in the Fremont and, for several years, the Horseshoe; Sahara owner Milton Prell and his partners built the Mint, whose general manager was veteran casino executive Sam Boyd, later a key downtown builder; former Flamingo and Riviera executive Ben Goffstein opened the Four Queens in 1966.

Fremont Street changed in other ways as well, thanks to two factors: the growth of Las Vegas and a revolution in transportation. While the Las Vegas population grew in the 1940s, it remained concentrated mainly in the vicinity of downtown. Even with new subdivisions, Fremont Street maintained its status as a meeting place for locals. They shopped at small stores, like Ronzone’s grocery and Hecht’s for clothing. Teens cruised the street on weekend nights and visited the nearby Round-Up Drive-In.

The changes in transportation had both local and national significance. The Union Pacific, which had bought out Senator Clark in 1921, replaced the old mission-style depot with a modern-style structure in 1940, with a city park beautifying the area between the depot and Main Street. But events were conspiring against train service as the predominant means of reaching Las Vegas. Federal highway building in the 1920s turned Fifth Street into part of the Arrowhead Highway, then Highway 91, from Los Angeles to Salt Lake. In this way, the land and water company finally fulfilled its twenty-year-old promise and paved Fremont all the way to Fifth Street in the mid-1920s. As the highway became more popular for travelers, other businesses began dotting Fremont Street near Fifth and in newer professional buildings, including law offices and accounting firms.

But the highway affected Fremont Street in less favorable ways. The stretch from Sahara to Tropicana—the Strip—gradually replaced the downtown casino district as a favorite stop for travelers driving from southern California. The construction of Interstate 15 west of the Strip and downtown enabled drivers to avoid downtown completely. Consequently, downtown Las Vegas—like many other downtown areas—grew seedier, with older, smaller casinos and more homeless people making it a poor second to the increasingly thriving and exciting Strip. Suburban developments appealed to longtime residents who could afford to move and to newcomers seeking more attractive neighborhoods, thereby draining downtown of its more elite population. From the late 1970s on, the growth of locals-casinos throughout the valley cost downtown many local visitors who had previously come there to eat, drink, and gamble, but now could do so closer to home.

By the 1970s, the era of the first photo in the Fremont Street montage the railroad depot was gone, replaced in 1971 by the Union Plaza Hotel from which the photo was taken. The neon signs, which Thomas Young and YESCO first erected at the Boulder Club in the 1940s, continued to light up downtown, but city officials led by Mayors Oran Gragson (1959-75), Bill Briare (1975-87), Jan Jones (1991-99), and Oscar Goodman (1999- ) made redevelopment and rebuilding a goal.

Their most notable successes are apparent as the photo of Fremont Street evolves. Over several decades, mayors and other political and business leaders discussed how to revive downtown, with possibilities that included Steve Wynn’s proposal to pipe in water to form “Las Venice,” complete with canals and boats. Goodman suggested a “Little Amsterdam,” with various forms of legalized vice popular in that European city and once common in Block 16.

But the centerpiece of downtown redevelopment proved to be the Fremont Street Experience. The $70-million project by noted urban designer Jon Jerde debuted in 1995. It features a canopy covering the first three blocks of Fremont Street, 12.5 million lights, 550,000 watts of sound, and a show every hour on the hour in the evening, along with free public concerts and an assortment of gambling, shopping, and entertainment. The photo shows some of the sixteen columns—weighing 26,000 pounds apiece—that hold up the canopy. After prolonged negotiations, the casinos agreed to dim their neon during the show.

Nor is Fremont Street’s redevelopment limited to the canopy. In addition to the block’s ten casinos and sixty restaurants, just east of the canopy is Neonopolis, a $100-million center with a fourteen-screen movie complex. West of the photo is a sixty-one-acre plot of land that now includes the World Furniture Mart and is the intended site of Las Vegas’s first true performing-arts center, the potential future homes of the Las Vegas Symphony, the Nevada Ballet Theatre, and various local and touring companies and programs. And, befitting its neon and history as “Glitter Gulch,” Fremont Street also hosts a Neon Museum of classic Las Vegas signs, recently kept in a “boneyard” a few blocks north.

Fremont Street is no longer the center of Las Vegas. Population growth surrounding Las Vegas has been so great that the center of town is now well to the west of the original downtown. The Strip is the main area for gambling and entertainment. But Fremont Street remains a historic part of Las Vegas and a key cog in the city’s effort to attract investment. As the light show suggests, the street—and its experience—beckon locals and greet visitors with “Welcome to Las Vegas.”

Some information reported here is sourced from Online Nevada.